The Horizon Glow-Up

Recently, I began a project to try to compare remote sensing data (multiple radar datasets with different wavelengths as well as thermal infrared from Diviner) to the ground-based data acquired by the only spacecraft to ever land on the ejecta blanket of a large Copernican (< 1 Ga old) lunar crater: Surveyor 7. This spacecraft landed on the northern edge of Tycho crater on January 10, 1968, the final of the robotic spacecraft sent to scout out the lunar surface prior to the Apollo landings. Surveyor 7 only contained three science instruments: the alpha-scatterer experiment, to get a crude estimate of local regolith elemental abundance; the soil mechanics and surface sampler, a simple pantograph-style robotic arm that could be extended and retracted to dig trenches to test the regolith’s geotechnical properties (bulk density, coefficient of friction, yield strength, etc.); and a television camera system with a clear lens and two polarizing filters.

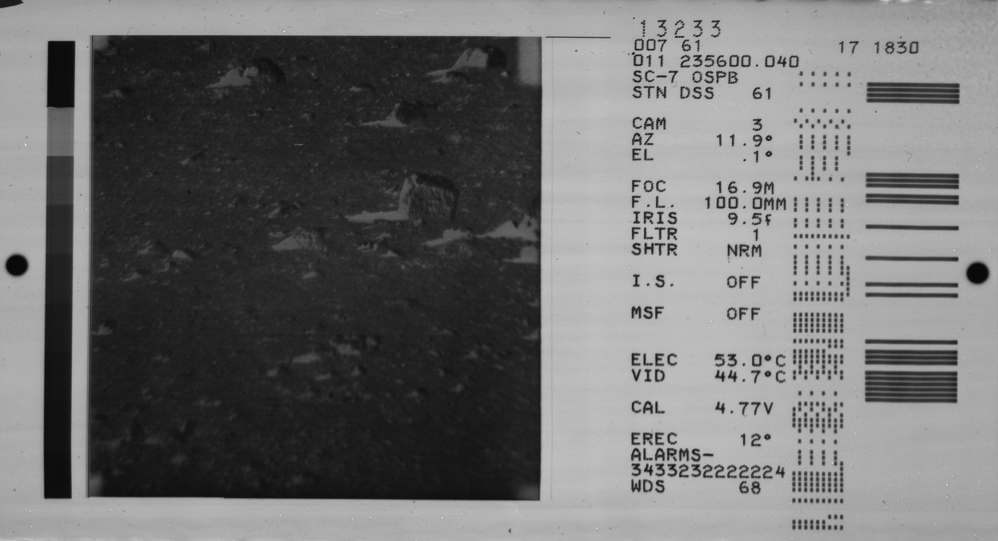

It was the last of these that became a potential avenue for new discoveries with this half-century-old dataset, after I stumbled upon the ongoing efforts of the Surveyor Digitization Project which aims to scan the archival film copies of the more than 80,000(!!) images taken during the Surveyor program. Several staff at the University of Arizona, as well as technicians with specialties in scanning film for archival purposes, have been working diligently since 2015 to turn these grains of film into bytes of data and translate all the metadata they were originally stored with in punch-card format.

Assisting them in this project is the venerable Jay Rennilson, one of the original co-investigators of the Surveyor television camera system, who is now well into his 90s and one of the last of the scientific team that developed these pioneering spacecraft. After emailing back and forth about the dataset and the specific images I was interested in examining, Jay mentioned his hope that someone would someday soon re-analyze the Surveyor data and send a spacecraft with similar capabilities and science goals to finally solve the mystery of the “lunar horizon glow”. And so today, I’m going to talk about his 1974 paper on the subject, the last time anyone has analyzed surface data to understand the properties of this mysterious phenomenon. Without further ado:

Surveyor Observations of the Lunar Horizon Glow (1974)

J.J. Rennilson and D.R. Criswell

The authors in this paper describe measurements of the lunar horizon glow, a phenomenon only observed by three of the robotic Surveyor probes which landed on various parts of the Moon between 1966-1968. This consisted of a very thin (~10-30 cm), low, horizontal band of light, visible just at or above nearby horizons in the subsolar direction for about 30 minutes to 2 hours after local sunset. The Surveyor probes were solar powered, but had batteries that allowed them to operate for some amount of time after sunset to conduct astronomical observations and observations of the lunar surface under Earthshine. The horizon glow was an unexpected additional phenomenon able to be observed due to this mode of operation.

The Surveyor 7 horizon glow is the best-measured of the three probes that saw it (Surveyors 5, 6, and 7, with hints that Surveyor 1 may have seen a similar effect). The horizon glow at this location was bright enough that the television camera could observe it in so-called “open” mode, where the photocathode tube that recorded the electronic signal was repeatedly scanned while the camera shutter was held open, resulting in integration times of ~1.2 s for each pixel. This was long enough to observe low-luminosity phenomena, while not so long as to cause the “smearing” effect seen in the much longer exposures (5 seconds to 200 minutes) taken in “integration” mode. The fact that the horizon glow still maintained a significant vertical and horizontal extent in open mode was cited as evidence that it was caused by a real local source, rather than a blurred astronomical phenomenon. Additionally, the fact that the contour of the horizon glow conformed even to small deviations in the horizon (e.g. rock 5 in fig. 1) was evidence that the phenomenon was not produced by some distant, ephemeral source stacked up over a large distance in western extent.

Many other measurements and data analyses (e.g., polarization, decay time, etc.) were performed to quantify and assess different possible explanations for the glow. The previously-mentioned points ruled out a vertically extensive source, in addition to the fact that the micrometeorite flux required to produce such an extended source is much greater than that observed. Additionally, the luminosity of the glow was low enough that it could not have been produced by an unresolved diffraction from a surface dust layer. (While a more extended, permanent, asymmetrical dust cloud has been observed by the LADEE spacecraft, this cloud is far too tenuous to explain the near-surface horizon glow, but may be responsible for a different, larger glow seen by Apollo astronauts and the Clementine spacecraft from orbit around the Moon).

The best explanation for the horizon glow put forward by the authors is an electrostatically-levitated curtain of tiny dust particles produced at the sharp boundaries between illumination and darkness that occur near sunset on the Moon’s airless surface. Their preliminary assessment of a model in which solar high-energy X-rays produce secondary electrons that escape and diffuse to dark areas suggests a voltage difference of 500-1500 V could be generated across these cm-scale boundaries, levitating the grains to heights of tens of cm. A forward-scattering model of large-sphere diffraction predicted that, for the solar phase angles at which the HG was observed (~3°), the average particle size would be on the order of 5-6 µm.

Over 40 years after this paper was published, and almost 50 years since the Surveyor 7 observations were initially acquired, a paper by Wang et al. (2016) experimentally demonstrated conclusively that particles up to several tens of microns could be levitated by electrostatic forces generated by solar radiation in an airless environment similar to that on the Moon.

To date, no landed spacecraft other than the Surveyors has directly measured this elusive and mysterious phenomenon, but this experimental evidence (and the model that explains it) adds significant weight to the hypothesis proposed by Rennilson and Criswell half a century ago. In a few years time, as robotic and human-crewed spacecraft equipped with far more advanced sensors are sent to continue humanity’s exploration of our planetary sibling, Rennilson told me he hopes he will finally get to witness the confirmation of his decades of persistent, meticulous, and pioneering work. I hope I can be there as well, and that my exploration of this data in its new, digitized form can extract even more exciting information from it. It’s not often in planetary science that we have data old enough yet well-preserved and unique enough to still be so valuable, a full half-century later. Working across this generational divide has given me a profound respect for the immense challenges the scientists and engineers of the 60s had to overcome to accomplish these astronomical (sorry) feats, and pride in being able to help transmit their stories and achievements to generations beyond.

Till next time!

-xoxo gossip grad