Let Me Reintroduce Myself (without apologies to Gwen Stefani)

As it’s officially the start of a new school year, I think it’s time for a status update on where I’ve been and where things are going next. This past year was an intense re-introduction to the unique working/learning/researching balance of academia, and one that I can’t altogether say I passed with flying colours. On paper, at least, I managed to keep my head above water, but I’m now entering the long dark phase of the PhD where the current slows, the shoreline recedes further away, and one must pick a direction to set off on their own. Or something metaphorical like that. Anyways, now that I’m through the roughest patches, I thought it might be good to start with a little more background about me and my work (à la my first blog post last year).

I grew up in Scarborough, a sort-of subsection of the larger city of Toronto, Ontario, and did my undergrad and Master’s degrees at the University of Toronto. (Normally I wouldn’t bother being so specific about my hometown, except that we now have our own movie and world-famous pop star, so it feels appropriate.) As I mentioned in my original introduction post, I’ve always been fascinated by space, and specifically the cosmic backyard of our solar system. People have asked me over the years how I managed to get interested in such a specialized field (rather than, say, just astronomy or geology more generally), and I think the real answer is that I was simply lucky enough to be born at just the right time to experience humanity growing up in our understanding of our home neighbourhood in space.

When I was three years old, comet Hale-Bopp was swinging by the Sun and treating the world to one of the most spectacularly visible dances across the sky in a century. Knowledge of the outer planets from Voyager was practically still brand-new information, and although that initial reconnaissance had already had its heyday before I came into the world, there was a new generation of robotic explorers that would continue to deepen our understanding of the fascinating, one-of-a-kind worlds of our solar system. Galileo, Cassini, Spirit and Opportunity, MESSENGER, Phoenix, and more would all become familiar names throughout my adolescence, and they transformed these planets from bright specks in the sky to immediate, vibrant destinations of their own.

Despite this, I almost didn’t end up in planetary science once I finally made it to university. I started out in the biology program, and thought my path might lead me towards ecology or evolutionary biology until a chance meeting with a professor in the Earth Sciences department during a pre-frosh week orientation session. He encouraged me to combine my interests in both space and biology, and that there was a whole field of people doing just that called astrobiology. One of Canada’s foremost astrobiologists worked in UofT’s Earth Science department, and although I never ended up working with her directly, the welcoming department atmosphere and some fascinating introductory courses in my second year sealed the deal.

It was during this time that I met the person who would set me off on the course to where I am today—Dr. Rebecca Ghent, who at the time was a professor in UofT’s Earth Sciences department. Although my undergrad final-year thesis focused on a hypothesis she had about volcanism on Mars, Becky was a member of many instrument science teams, and in my second year introduced me to the folks running the Diviner Lunar Radiometer, a thermal infrared instrument onboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. It was this that would prove to be fateful—and lead to what I’m still working on to this very day.

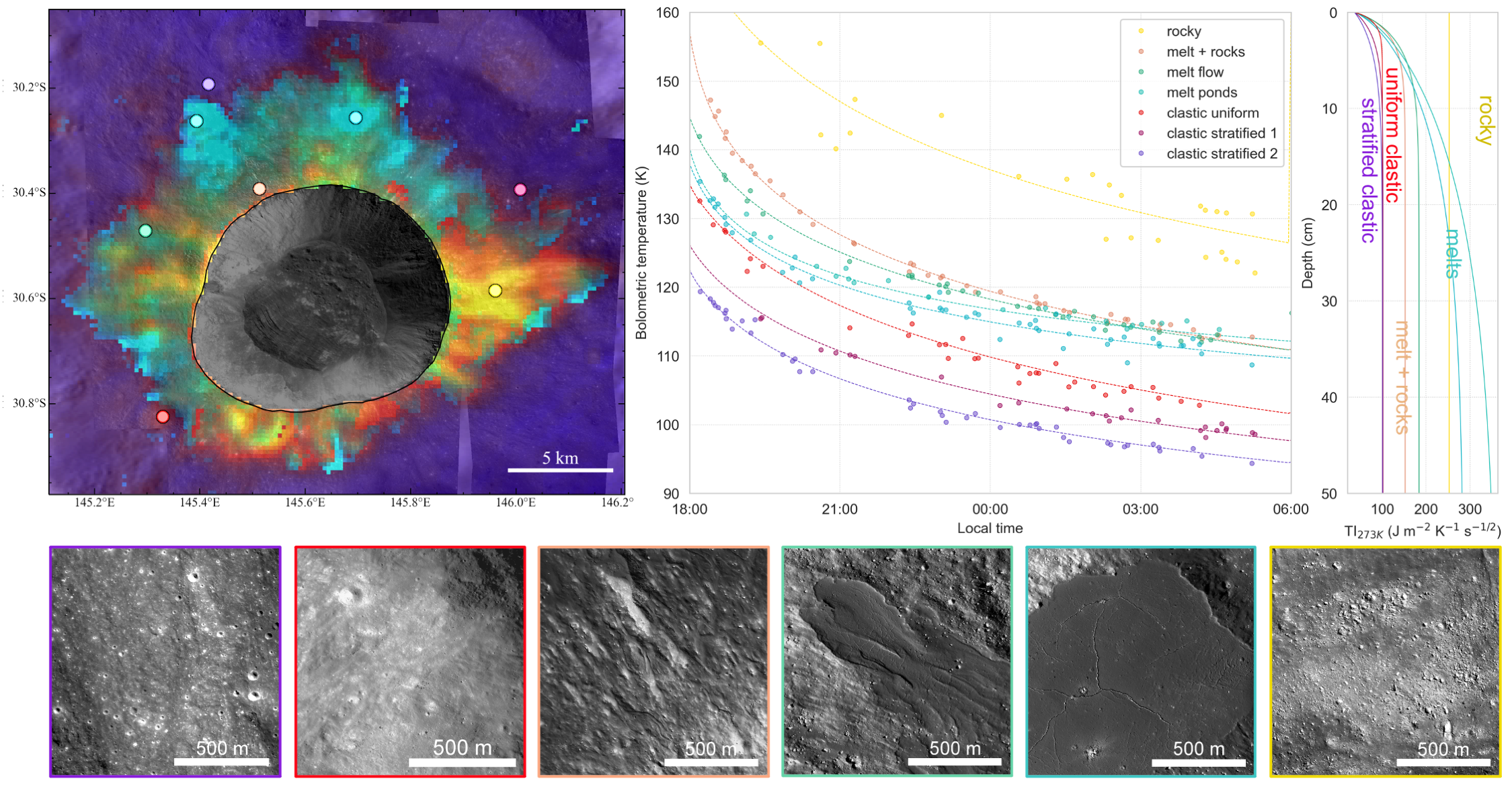

So, to get to my research! I’m currently using Diviner data to study the thermophysical properties of lunar impact crater ejecta, and specifically trying to disentangle the physical properties of boulders and rocky ejecta vs impact melt. As an example of the kind of data I’m using, here’s a plot of derived nighttime surface temperatures for two locations around the young lunar crater Tharp compared to the standard thermal models that have been used in the past to fit them:

As you can see, none of the model curves fits particularly well. That’s where my work comes in! I’ve been able to develop a new two-parameter thermal model that can vary the subsurface density profile at every given spatial bin, and then an algorithm that can robustly choose the best parameters. These can then be turned into an RGB map of the physical properties by mapping the difference in temperature between early and late night to red, the rate of transition from low to high density with depth in blue, and the bottom density of the model in green:

If you’re curious to learn more, I have a few previous posts going over the many, many gory details needed to produce these maps, and I’m still trying to finally finish my paper wrapping up performing this on many craters throughout the Moon and seeing what patterns and trends emerge. When that’s finally done, I’ll be sure to give a full update!

Till next time!

-xoxo gossip grad