Divination Explanation

Okay, I get it, y’all are probably tired as hell of me blabbing on about “LRO this” and “Diviner that”, but today I thought I should give an overview of just what the hell exactly these spacecraft/instruments are, and context for how they got to where they are today. No wait, don’t leave! I promise it’s really interesti—

…welp, alright, now that those people are gone, I guess it’s just you info freaks left—and I’m sure you wanna hear the rest of this tale! So, here goes:

It all started a long time ago, in a decade far, far away…

It was January, 2004. President George W. Bush was in the prime of his two-term tenure, nationalism was at an all-time high, and the botched invasion of Iraq in search of non-existent WMDs had yet to be fully unveiled for the fraud that it was. Sensing a potential downturn in public approval, and hot on the heels of the space shuttle Columbia disaster the year before, Bush announced a bold new plan to return to the Moon that would hopefully reinvigorate some of that Apollo-era space-race enthusiasm: the Vision for Space Exploration.

This was a proposal to return humans to the Moon by 2020, after retiring the Space Shuttle in 2010, and with an intended initial robotic exploration of the Moon from orbit by 2008. At some point in the future beyond the second decade of the new millennium, there would be an intention to send humans to Mars. Many people, including Buzz Aldrin himself, were skeptical of the need for such a return of humans to the Moon, and into deep space in general, given the success of robotic planetary exploration missions since the end of Apollo, and the immense investment that would be needed for a human-lifting rocket capable of rivalling the Saturn V.

Regardless of one’s feeling on crewed vs. uncrewed exploration (and yes, that’s the NASA/ESA-approved correct term, ya red-pilled dinguses), the Vision for Space Exploration was a boon for lunar research. Since Lunar Prospector deliberately de-orbited (the technical term for “went kaboom”) in 1999, NASA had no resources, robotic or otherwise, exploring our closest planetary companion. While it was claimed that Prospector and the previous Clementine spacecraft had achieved their goals by detecting water in the permanently shadowed regions of the Moon, the evidence was later deemed inconclusive, and there were still many unanswered questions about the Moon’s nature and origins.

Enter LRO: in 2006, the spacecraft completed its preliminary and critical design reviews, and it was slated to be the first step in the Bush administration’s lofty goals for human lunar settlement. On June 18, 2009, after many years of integration and testing, LRO made it to the launch pad, only 1 year behind schedule (not bad by NASA standards). In a flash of fire and smoke, the Atlas V rocket—with the comparatively tiny spacecraft and its companion, LCROSS, perched atop—roared to life and blasted off the Florida coast. Next stop: the Moon.

The twin spacecraft had a single primary goal: confirm the detection of water in the Moon’s permanently shadowed regions, by smashing an empty rocket upper stage into the dark depths of Cabeus crater near the south pole, and observing the resulting impact plume with their suite of instruments. In this, they were successful—but for LRO, the mission had just begun.

One of the key instruments in observing the LCROSS impact and detecting evidence of water in the resulting plume was Diviner (look, we finally got there!) Nearly an identical copy of the Mars Climate Sounder (MCS) instrument on the equally-uninspiringly-named Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, Diviner is the brainchild of Principal Investigator David Paige, who, along with several other original team members, took to the task of modifying the original MCS design for the Moon.

Mars Climate Sounder has 9 channels like Diviner, but they span a different range of wavelengths. At Mars, MCS was primarily designed (as its name suggests) to probe the structure of the Martian atmosphere. Therefore, the 9 channels were chosen so as to span the expected range of temperatures in the atmosphere (15.4-27.1 $\mu$m), with specific bands chosen especially to sense the presence and quantity of water vapour in two spectral bandpasses (41.7 and 42.1 $\mu$m). Additionally, the detectors had to be miniaturized compared to previous thermal infrared instruments on interplanetary spacecraft, which were traditionally quite bulky from utilizing an interferometer for high-spectral-resolution measurements. MCS would need to scan the limb of Mars as well as pivot to obtain nadir observations using a two-axis azimuth-elevation mount, meaning the whole assembly had to fit on a platform capable of pointing rather quickly. Thus, the MCS team utilized small thermopile detectors with micro-mesh filters over them, a solution that had been used on other thermal camera systems before, but never an interplanetary spacecraft. Finally, the 9 channels were divided between two telescopes (A and B) comprising the MCS focal plane, giving MCS its characteristic WALL-E-esque look:

Diviner, on the other hand, would be operating on an airless body with temperature swings wildly higher (127$^{\circ}$C vs 20$^{\circ}$C) and lower (~$-$250$^{\circ}$C in polar cold traps vs $-$153$^{\circ}$C) than those on Mars—thus, the wavelength range of the filters needed would have to be much broader than MCS’s. Additionally, since it wouldn’t be sensing suspended water in an atmosphere, Diviner’s compositional channels were free to be altered from those on MCS. The choice was made to place three of the channels near the 8-$\mu$m Christiansen feature (CF), a spectral peak in emissivity associated with the silicic composition of rocks and powdered materials in vacuum. This peak is dependent on the polymerization state of silicate minerals; thus, highly-polymerized materials such as feldspars exhibit CF peaks at shorter wavelengths than less-polymerized silicates like pyroxene and olivine.

The final filter selection for Diviner therefore encompassed two broadband solar channels for measuring surface albedo and total reflected light, three Christiansen feature channels for studying silicate mineralogy, and four thermal channels that spanned the wavelength range (~12.5 $\mu$m-400 $\mu$m) necessary to determine the highest and lowest temperatures on the Moon.

Additionally, since Diviner was meant to be primarily a nadir-pointing mapping instrument, the elevation-azimuth mount for the optical bench assembly may have been forgone. However, since the primary benefit of Diviner’s design was that it was essentially a copy of MCS, the decision was made to include the two-axis mount, mostly to allow calibration of surface temperature measurements through intermittent measurement of an internal blackbody target and a well-characterized solar-reflecting surface. But it turned out that this choice became instrumental (ha) in Diviner’s past and ongoing success as a 12-year-old sciencing machine. The freedom to point Diviner in a range of orientations relative to the spacecraft meant that Diviner could still take measurements when LRO was rolling or slewing to acquire off-nadir observations with its other instruments, something the rest of the instruments just had to go along for the ride with.

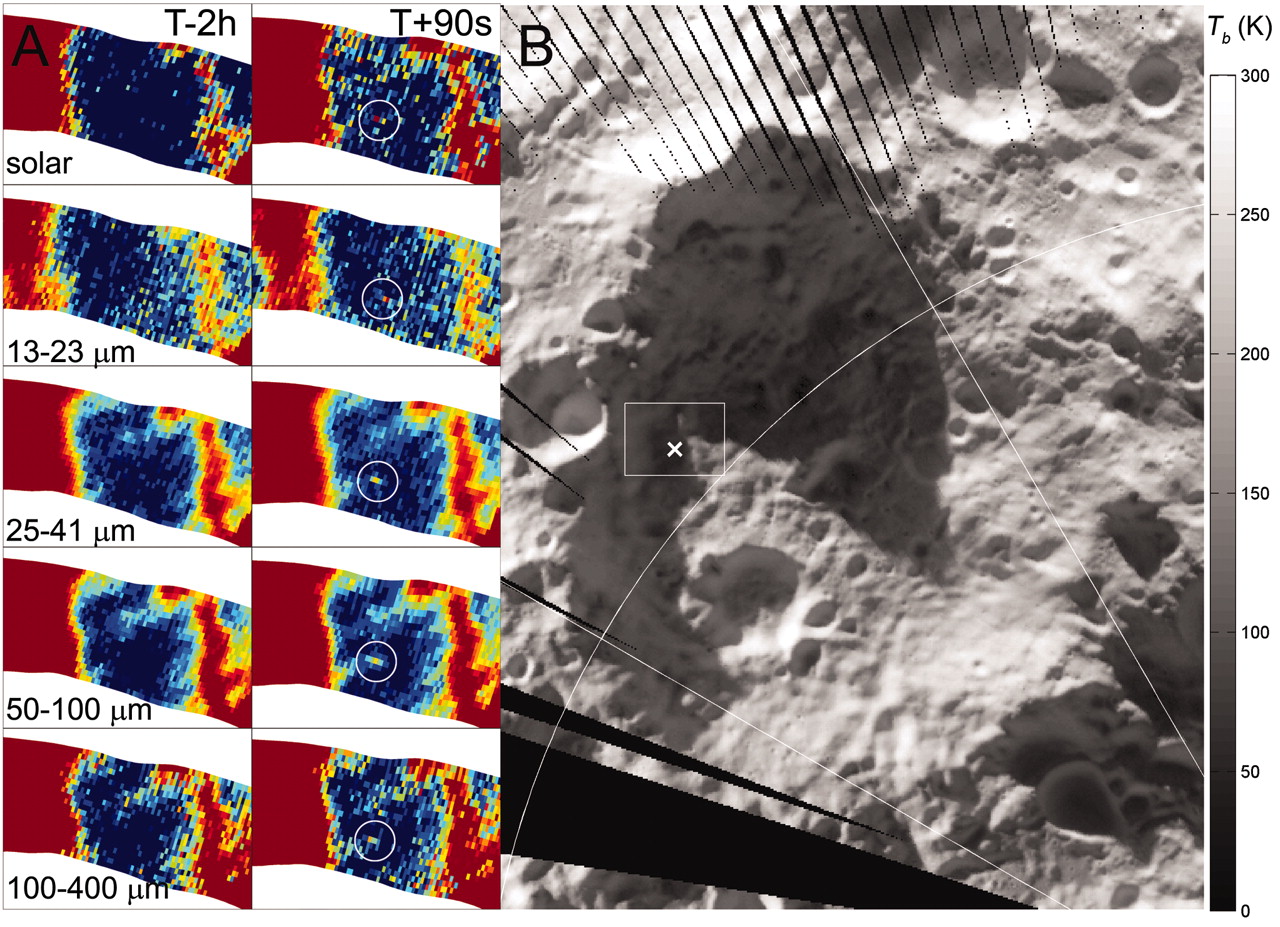

This was first put to use when Diviner was able to measure the thermal glow of the LCROSS impact, and therefore constrain estimates of the size of the crater produced and the amount of water in the resulting ejecta plume. Since that time, Diviner’s off-nadir capabilities have proven to be invaluable assets for the ongoing success of LRO. During lunar eclipse, Diviner has been able to point at targets off its nadir track over multiple successive orbits to measure the rapid near-surface cooling that occurs during these events, along with measuring the directional emissivity and obtain estimates of the roughness of the lunar surface by building up an “emission phase function” by observing certain targets at many different angles.

This pointing capability, however, has also proven to be somewhat of a woe: last summer, it was discovered that Diviner was suffering from a very small but significant pointing anomaly, which meant that observations of sub-pixel thermally-bright targets were not able to be co-registered. After measuring the offsets between the expected and measured positions of a large number of these targets across the Moon, the team was able to come up with a temporary fix that has significantly improved our data quality:

The difference is remarkable, like putting a pair of well-tuned spectacles on our old WALL-E-shaped friend. The consequences of this fix will also be extremely significant for processing of Diviner data by other researchers, including those diving into the massive archive of data from it long after the mission has finally ended.

So that’s the story of how the little thermal scanning robot that could came to be. Before starting to work with it, I never really realized how incredible of an instrument Diviner is. I had never heard of the way other thermal instruments worked on other spacecraft, but I knew they generally produced low-resolution images that looked like they had to be interpolated in some way instead of just representing a raster of the observed temperatures of the surface. Diviner’s ability to do this, and in unprecedented detail at the Moon, has enabled dozens of investigations that would not otherwise been possible with alternative designs. My hat goes off to the design, engineering, testing, and scientific team that came together to create this magnificent heat-seeking machine.

Next time we dive back into research land again: an overview of how to process Diviner data to get all of the wonderful products that people have been able to derive from it, as well as a few dives into the specific ways I’ve been working with it to contribute to the overall science team productivity.

Till then,

-xoxo gossip grad ☾⋆⁺₊⋆