Asymptotic Intelligence

AI is growing smarter by feeding it the internet. What happens when it starts to consume itself?

Note: this post is definitely not the first time someone has had this particular take, and while writing I came across this blog post that hits on many of the same key ideas expressed here. However, I’m hoping I can expound upon it and bring in some additional ideas that will help push the conversation on this aspect of our AI-infused future forward.

Everyone and their mother has written an opinion piece on ChatGPT, the harbinger of the great impending text-induced technosingularity of our time, but this week we’ve been asked to write a blog post about it, so, here we are. However, I’m hoping we can delve into some broader philosophical and technological implications associated with the advancement of AI in the near future by focusing on a particular aspect of these ever-ballooning language models: their input source.

The general features of AI are well-known by now: they have to be trained towards a particular task; there needs to be a reward or feedback mechanism to evaluate how good they are at that task; and mostly importantly, they need a lot, lot of training examples to fiddle their internal optimization knobs until they slowly converge on optimal performance at that task. The general sense in how this training is accomplished has been explained much better by others than I could ever hope to, so click that link if you’re interested in the details. But the salient point right now is that essentially, the more data you have, the better the output of your model should be, at least in theory.[1]We’ll come back to the caveats around this a little later on.

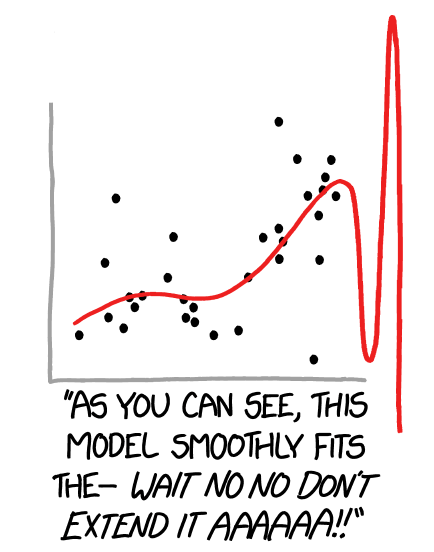

This last point is partially what’s made me less afraid of AI coming to take my job than people in most other computer-based occupations. In order to avoid the terror of “overfitting”, where your model is trained extremely well on your training dataset but utterly fails when given new input it’s never seen before, you have to have both the initial massive bank of data to perform the training on, and an additional set of data against which you can test the performance of your model. In the field of planetary science, there actually aren’t that many catalogues of data large enough to be useful for both the initial training while still reserving a sufficient quantity for model-validation purposes. In many other domains, however, the common fear is that our modern internet-connected world has given us too much data for standard techniques of the past to be able to cope with it all and turn it into useful insight. This has led to the rise of “Big Data” as a term of art in computer science in the past decade, and while methods in this field don’t necessarily have to incorporate machine learning/AI/neural networks/etc., in practice they have become the first tools that many researchers reach for.

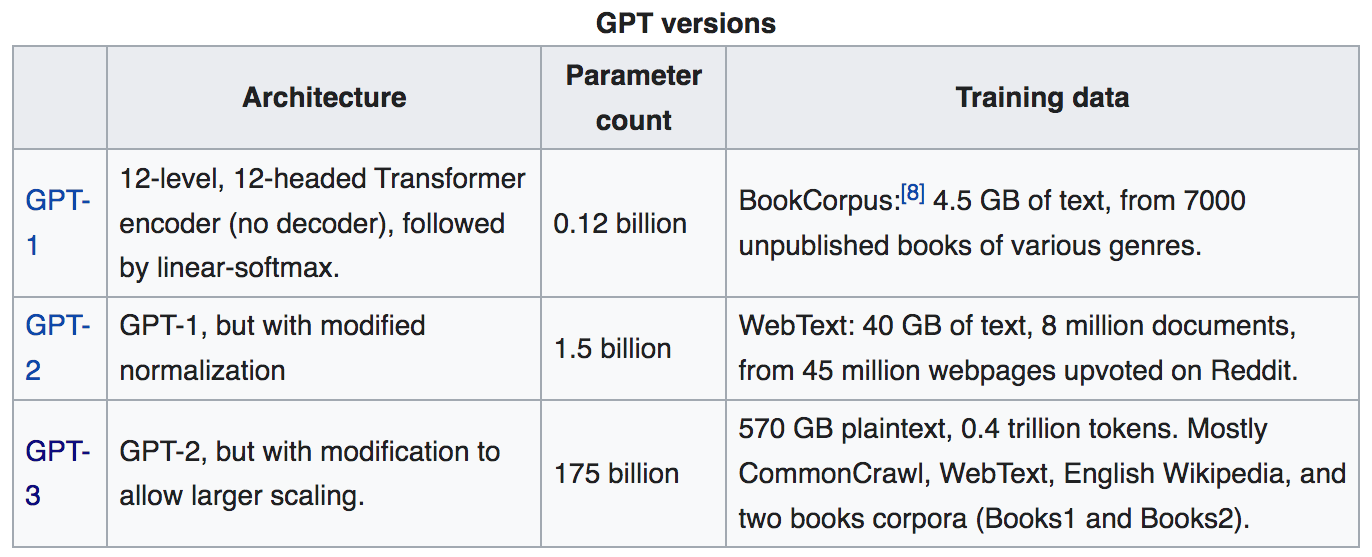

This brings us to ChatGPT. The now-ubiquitous chatbot is actually a specially-trained version of a simpler (but still incredibly sophisticated) type of machine learning model known as a “transformer”, initially introduced by the company OpenAI in the form of their General Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) family back in 2018. ChatGPT is based on the third generation in this family, GPT-3, which was already starting to make headlines back in 2020 for its uncanny ability to generate (mostly) human-like writing. But reach into your pocket and you can find a machine-learning tool that will also generate large amounts of semi-coherent text in the form of autocomplete (leaving aside whether most it makes any damn sense). So what makes ChatGPT different?

The first answer is the way it’s been trained. Compared to a task like image recognition or classification, the end-goal of ChatGPT—being able to take in any query or prompt from a human, parse and understand it, and then respond in an appropriate manner—is incredibly open-ended and difficult to quantify. How do you know when you’ve had a “good” chat session? How can you assign a number to that session which can be used to give feedback in a way that a computer would understand? Additionally, even if you can find a way to quantify such a conversation, you aren’t necessarily guaranteed that your quantification scheme will actually train your AI to “think” in the same way a human would, since it is not directly optimizing for the same goals as humans—being helpful, friendly, truthful, and so on. This is known as the “AI alignment problem”, most classically demonstrated by the “megalomaniacal stamp-collecting robot” thought-experiment, and it has been one of the most significant problems both in general AI ethics research and in actually improving the performance of natural language processing (NLP) AI systems for the past 30 years.

ChatGPT solves this problem by eschewing any attempt to systematically quantify its outputs according to some rubric or measurement scheme. Instead, it relies on the end-users who will actually be interacting with the model to be the feedback mechanism themselves: humans. While humans are terrible at assigning consistent quantitative values to complex or subjective assessments[2]See: me every single time I try to mark assignments fairly 😭, we are incredibly good at spotting things that just seem “off” in conversations, and at ranking a small set of alternatives according to our subjective preferences. So, using the underlying language model (GPT-3) to generate a set of potential next responses based on a human-to-human chat conversation, the architects behind ChatGPT set out to get a computer to do the scoring job for us, by training a second model to learn to predict which of those choices a human would generally rank highest, a procedure known as “reward modelling”. The numerical value output by this second model could then be fed back into the first model in order to give it a score to optimize against, and this process could be repeated thousands and thousands of times without the tedious (and slow) work of scoring needing to be done by humans every time. The combined strategy of human ranking of initial human-generated examples, followed by training of a feedback bot that then can be the scorekeeper for the text-generation bot, is known as “reinforcement learning from human feedback” (RLHF), and it is the secret that has unlocked GPT’s massive potential.[3]Two excellent videos that explain this process in more detail are this video on ChatGPT by Computerphile, and this video that dives more into the nitty-gritty details for those with a background in general machine learning/neural network/transformer architecture.

However, the second answer to ChatGPT’s success is somehow both obvious and stupefying: it is simply way, way, way larger than any other language model before it. To give you a sense of scale, keeping in mind that the first iteration of this language model family was released less than five years ago, here is a table of the number of parameters and input corpus sizes for the current lineage of GPT models:

Now, size alone does not guarantee an increase in a language model’s success at mimicking human-like text output. In order for an increase in, say, the number of parameters in the model to be useful, the model also needs a corresponding increase in the amount of training data it receives to actually be able to use those parameters to extract new information. Conversely, an increase in the amount of input training data without a concurrent increase in the model parameter space will mean the model just does not have enough knobs to tweak to capture the complexity of all that data. And, as explained above, both of these variables can be inadequate at getting your model to actually do what you want it to do if the goals you give it are misaligned with the goals you desire from it.

(meat of the post, explaining the issues with ChatGPT-generated content being fed back into training data, and correspondences with the problem of SEO-optimized auto-generated spam clogging up Google searches)

The prospect of “running out” of sufficient training data to improve language models is not just a thought experiment or hypothetical: there have been real concerns raised by multiple researchers about future limitations on training dataset sizes in the relatively near future. Although the total corpus of text produced on the internet since the birth of the World Wide Web in the early 90s is massive[4]even if only considering the subset of all text ever posted that’s both a) still available online and b) searchable via web crawlers, the amount of high quality data—that is, data which has been screened and tagged for violent or otherwise undesirable content, cleaned of any unavailable glyphs or other errors in rendering, and de-duplicated—has been asymptotically approaching a plateau since (some time), as the work necessary to make the firehose of information actually useful has increased exponentially. While just a few years the major concern of the modern internet age was the information overload and inability for any one person or even group of people to consume and process that volume of data, we now see ourselves staring down the opposite barrel: a machine learning system with an endless hunger for more, consuming at superhuman speeds, that will soon overtake our feeble abilities to generate new thoughts and ideas—even from all 8 billion of us.

Even before we hit the training data ceiling, however, there is an even more pressing issue facing AI research: now that text-generating language models have been unleashed to the public and made easier to access than ever, what will happen to that growing corpus of text as it becomes populated with their own output? This is the problem pointed out in the blog post I mentioned at the beginning of this post by Daragh Ó Briain[5]Yes, that is spelled correctly, there is no apostrophe—and apparently there is an amusing story behind this which I will never know, an expert in data quality, data governance and information management, who delightfully termed it the “Enshittening of Knowledge”.

In fairness, this degradation

These models do not work like human brains, which can extrapolate from a few small examples and make large logical leaps by connecting disparate learned concepts and synthesize these into novel understanding. Rather, they are essentially an enormously scaled-up [something], drawing from a hundred-billion-dimensional prior and guessing what [something something]. In order to make better predictions, these [blanks] need exponentially-increasing amounts of training data. That means they can only ever be proportionately as good as the corpus fed into them, and how carefully that corpus is curated to encourage the desired traits in the final trained model.

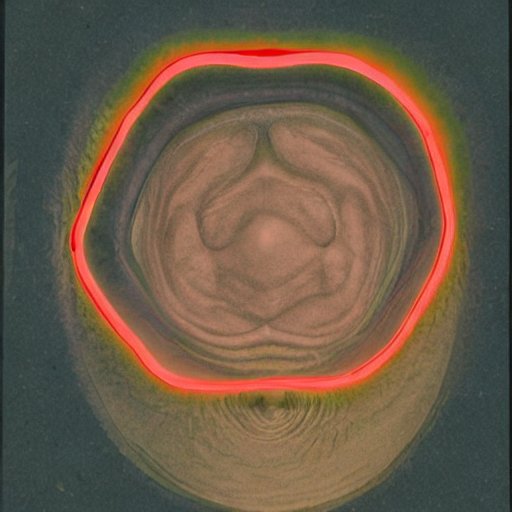

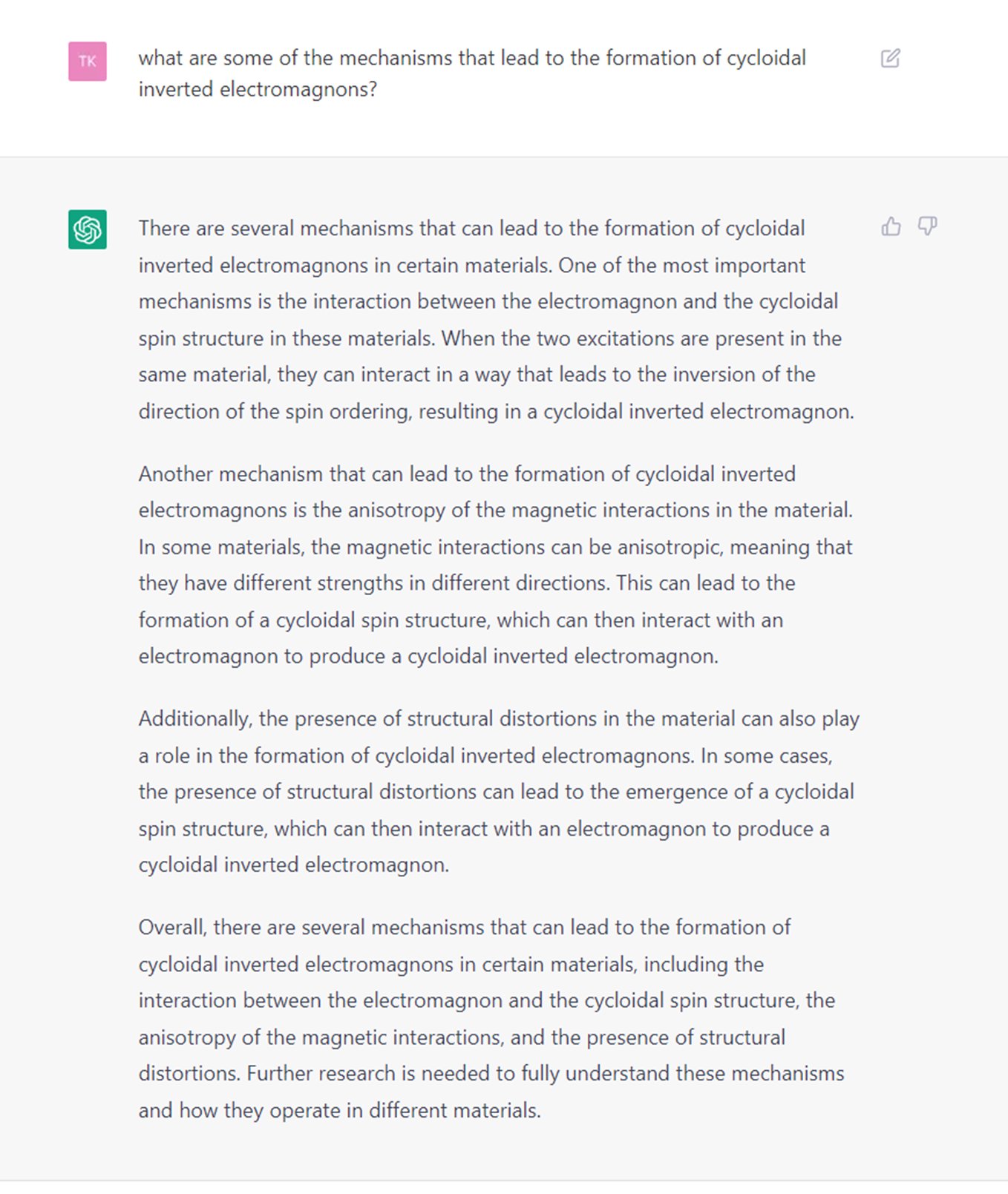

One of the first times I saw it come up in the context of scientists considering it a serious issue was this tweet, which started off by talking about its familiar issues with hallucinations that in this case resulted in made-up papers with made-up authors on a subject it mostly BS’d or wrote only very vaguely about. But this follow up further down in the thread seemed to indicate that, to this researcher at least, its answers were good enough to convince even seasoned experts that the nonsense it was dreaming up in its bit-addled mind could possibly be mistaken as real. But could it? While I’m not personally a researcher in the field of solid-state physics, I read one of the “spooky” screenshot examples and, well, I’ll let you see for yourself…

To me at least, the repetitions and vague phrasing, using the same jargony terms over and over without really delivering any new insight into any of them, plus its usual 8th-grader 5-paragraph response format would have immediately set off my BS detector. But hey, I didn’t ask it about the thermophysics of lunar granular media, so who knows, maybe it actually would spook me if I was familiar enough with whatever technical terms it tried to use in its bamboozling attempt and applied them semi-accurately.

Resources:

This quote from the hacker news discussion on the original blog post:

“I don’t really understand this hypothesis as it assumes that information quality of AI generated content on the internet will drop as a result of ChatGPT, not increase.” It has to drop. ChatGPT can not source new truths except by rare accident.

I bet a lot of you are choking on that. So, I’d say this: Can you just “source” new truths? If you just sit and type plausible things, will some of them be right? Yes, but not very many. Truth is exponentially exclusive. That’s not a metaphor; it’s information theory. It’s why we measure statements in bits, an exponential measure, and not some linear measure. ChatGPT’s ability to spin truth is not exponentially good.

A confabulation engine becoming a major contributor to the “facts” on the internet can not help but drop the average quality of facts on the internet on its own terms.

When it starts consuming its own facts, it will iteratively “fuzz” the “facts” it puts out even more. ChatGPT is no more immune to “garbage in garbage out” than any other process.

“Finally, I think what you’ll see happen in future iterations of ChatGPT to improve quality and accuracy is that content will be fed in weighted by how authoritative the source is”

Even if authority is perfect, that just slows the process. And personally I see no particularly strong correlation between “authority” and “truth”. If you do, expand your vision; there are other “authorities” in the world than the ones you are thinking of.

Hacker News user jerf

new scientist article about limits on quantity of training data