Near the end of last year, my first ever first-author paper was finally published. It was a culmination of four years’ worth of work, and although a fulfillment of one of my greatest life goals, it came at a rather unfortunate time in the semester when TA work once again nearly destroyed me.[1]Mentally and physically—thankfuly I’m mostly okay now If you’re interested in all the gory, dry, science-y details it’s available free and fully open-access here. But today I wanted to talk about a different, parallel saga that accompanied this long effort towards scientific publication: naming one of the craters I analyzed in it.

When any surface feature on a planet gets discussed enough in the literature, the IAU may consider it appropriate to give that feature a formal name. These names usually must conform to a set of strict rules depending on the feature type and planetary body, but in general, any scientist can submit a name for consideration (including grad students, I discovered, as long as they have a letter of support from their supervisor). So, a little over a year ago, I sent in an application to the IAU detailing every time one of the unnamed craters in my study was discussed in past literature, as well as a suggestion and justification for whom it should be named.

On March 4, 2024, that name became official: Mirzakhani Crater.

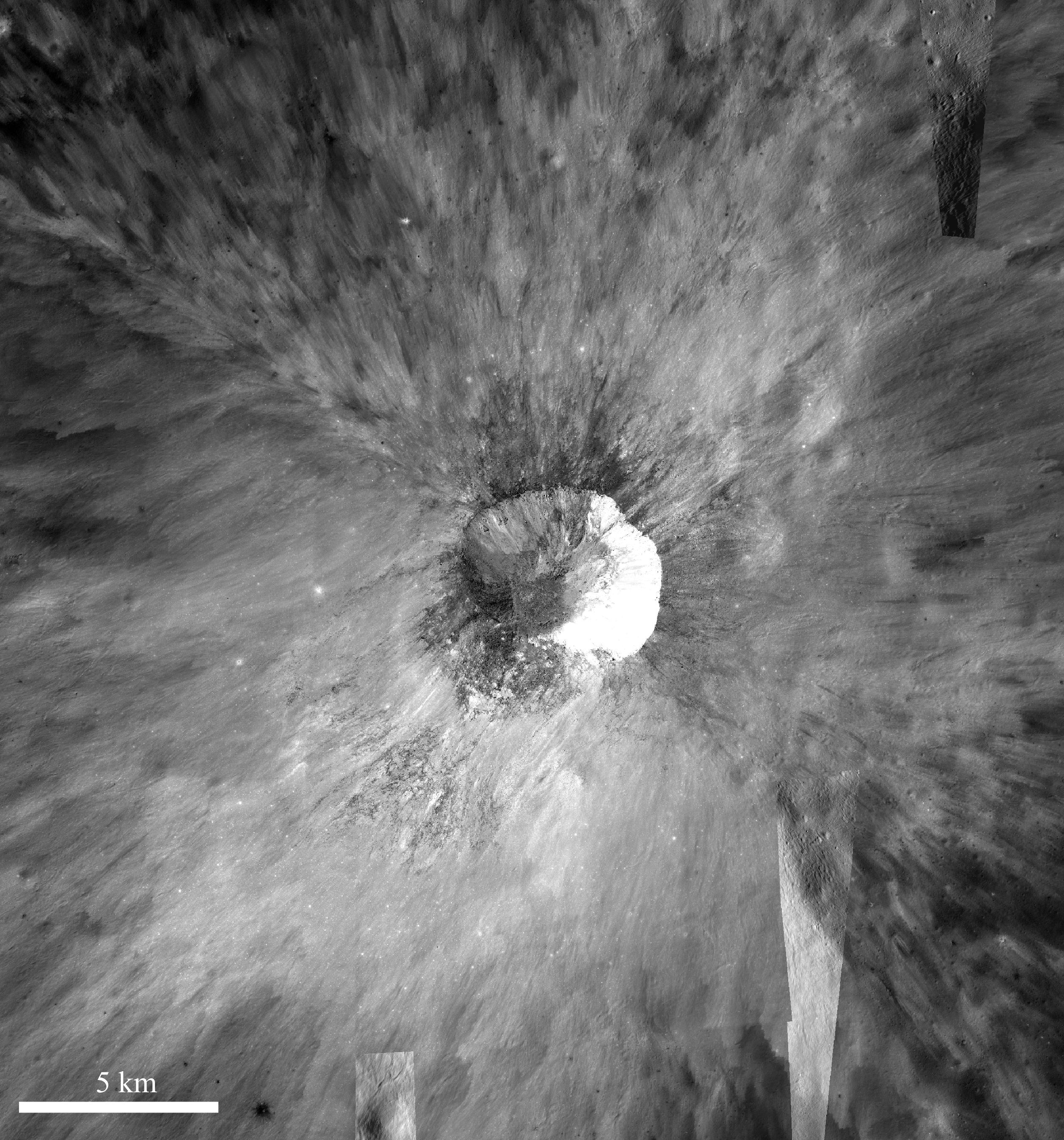

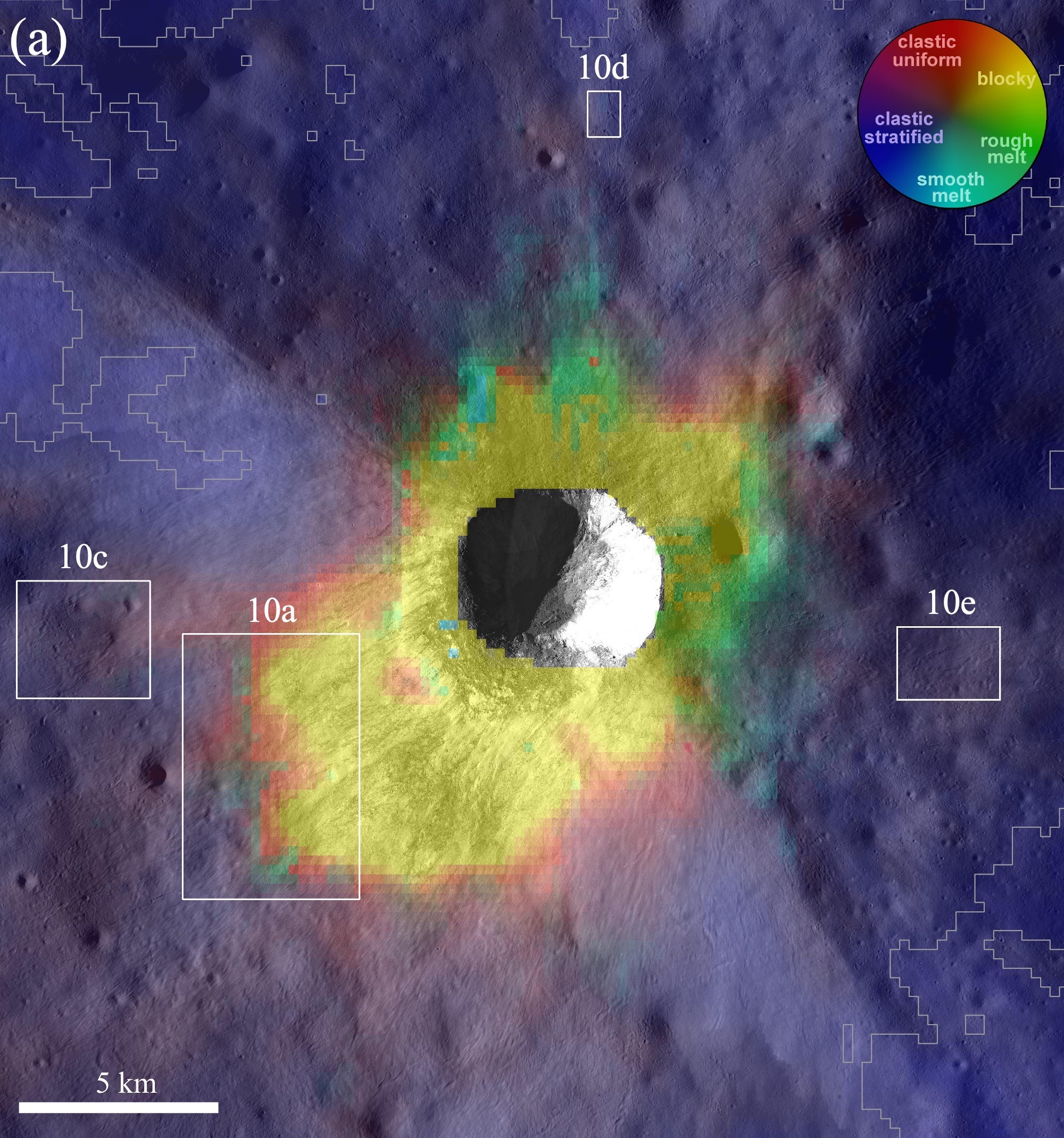

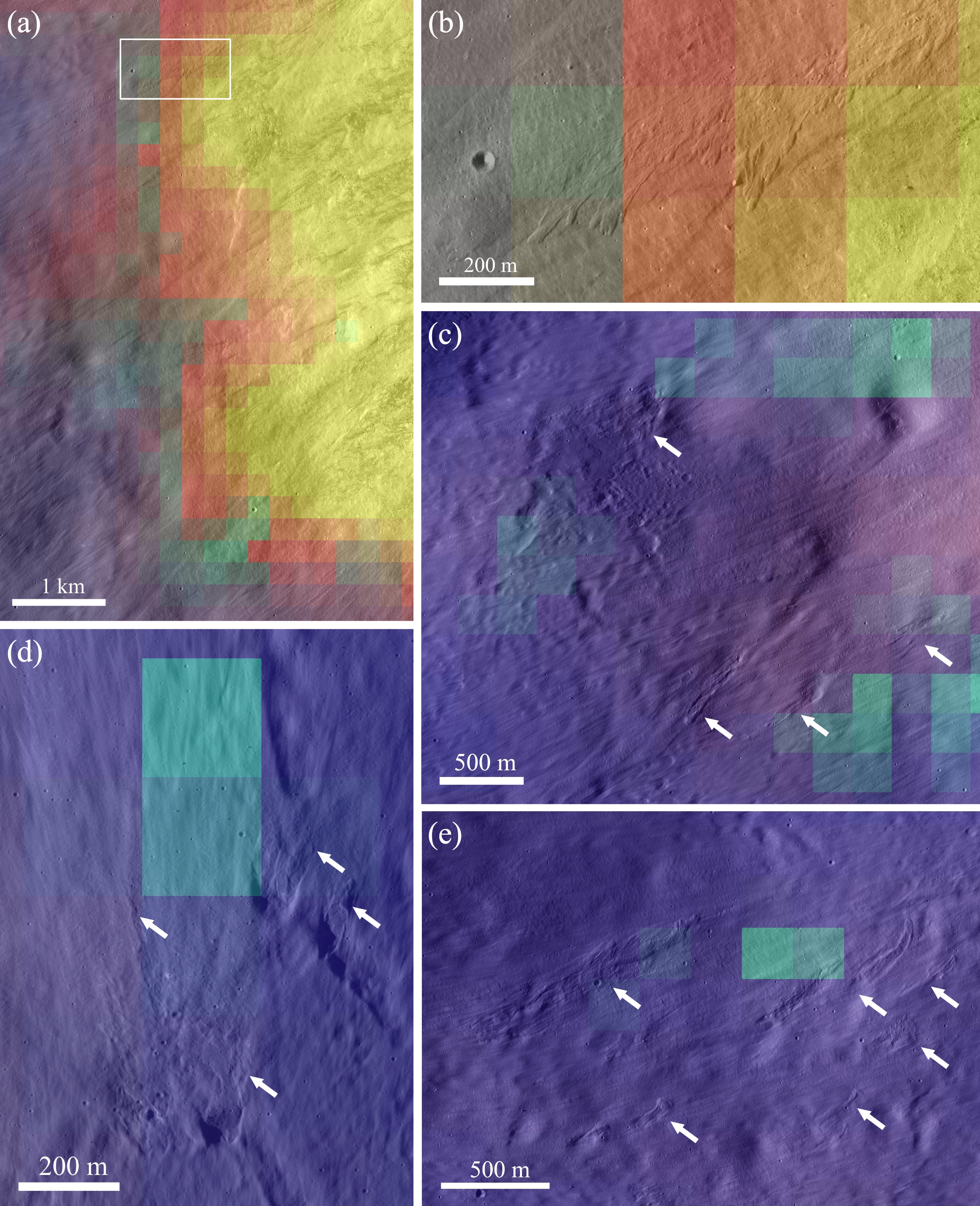

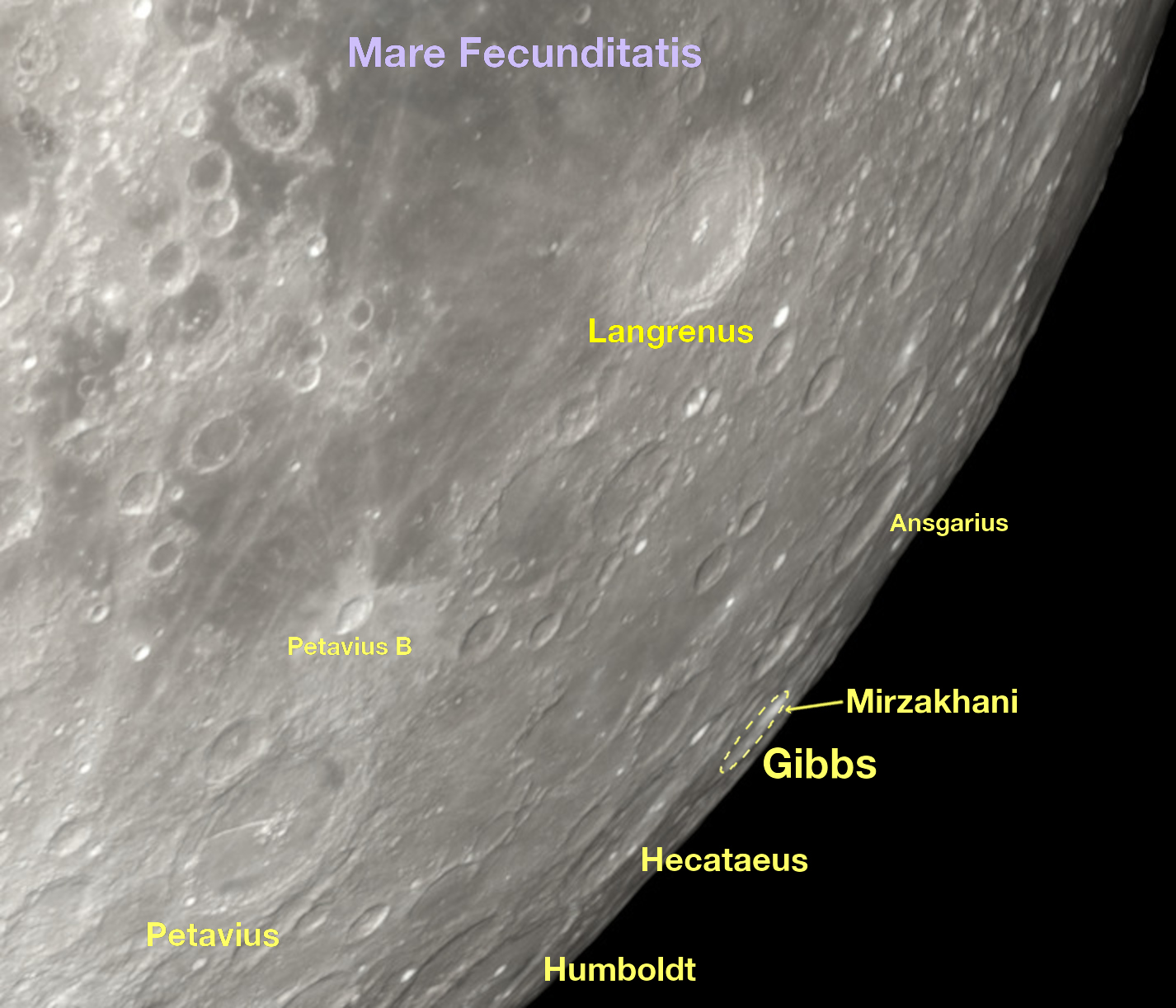

At just 5 km across, Mirzakhani is the smallest crater I discuss in my paper, but despite this humble diameter its bold, bright streaks of ejecta are already teaching us much about the nature and physical processes of asteroid impacts. At this small scale, Mirzakhani wouldn’t be expected to produce significant amounts of impact melt based on our best computer models of impact shock physics—and yet here it was, glowing with the thermal signature of visually-elusive melt flow deposits in areas well beyond the striking dark streaks near its rim.

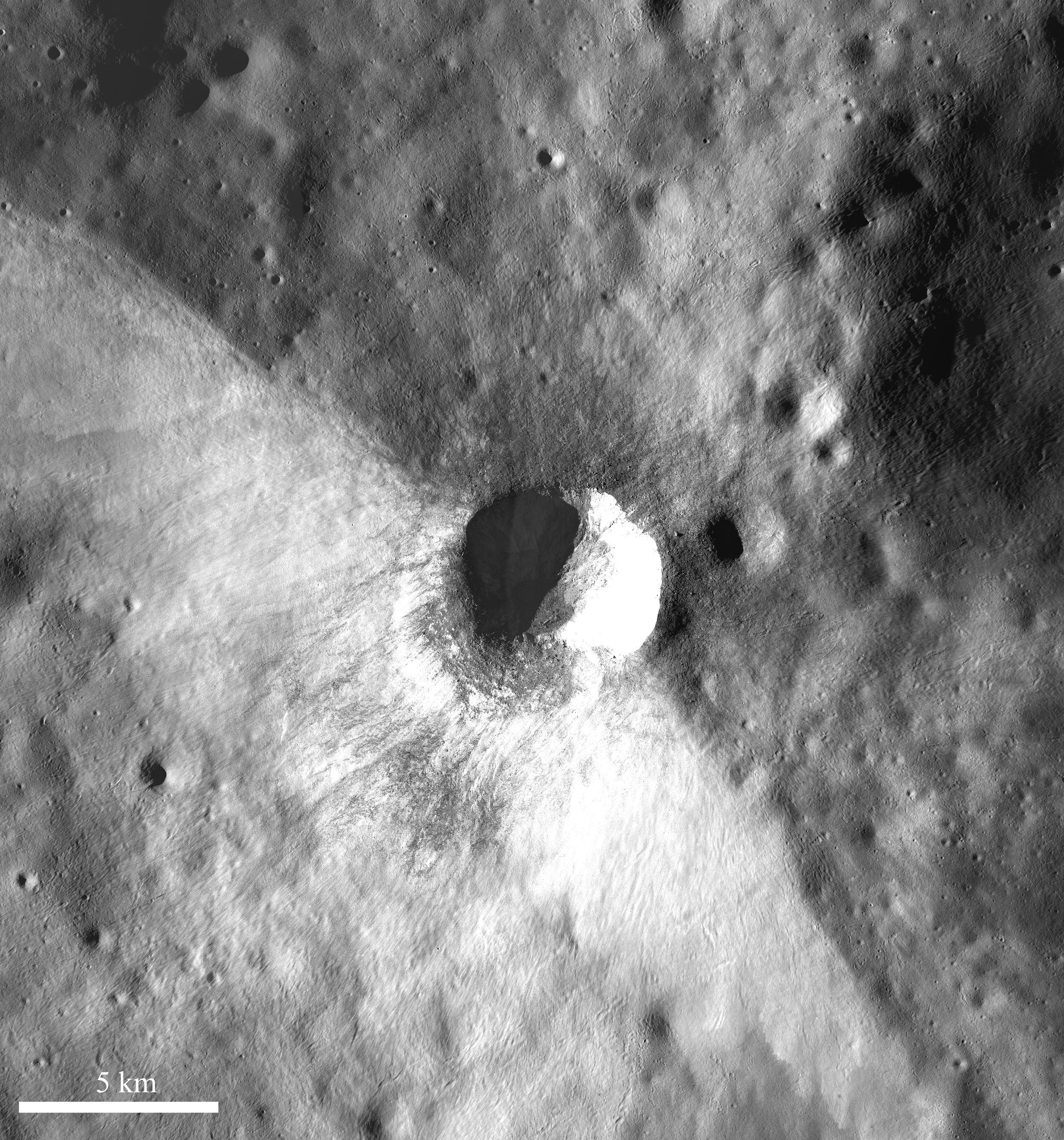

For a bit more context, here’s some of the surrounding area of the Moon, including a full view of the large crater Gibbs on which Mirzakhani formed:

Fortuitously, Mirzakhani is also located at 17.47°S, 85.20°E—juuuuuuust barely on the nearside,[2]Which covers up to a maximum of 96° east/west of the Moon’s center-point as viewed from Earth, due to libration meaning if you had a really powerful telescope (and the right lunar phase/orbital conditions) you could technically see it in your own backyard!

What’s in a name?

If you aren’t aware of her, Maryam Mirzakhani was an Iranian-American mathematician, a brilliant and —— ——, and the first woman to ever win the Fields Medal (basically the Nobel Prize of mathematics) back in 2014. Unfortunately, she could not bask long in that achievement, as her life was tragically cut short by cancer in 2017.

There were many reasons I thought this name felt appropriate: for one, there are very few craters on the Moon named after women, and even fewer after women of colour—only three others previously, as far as I could tell.[3]Those being Kalpana Chawla, STS-87 mission specialist who tragically passed away in the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster; Annie Easley, computer scientist and mathematician who made contributions to the design of the Centaur rocket, and one of the many African American women working as “human computers” at NASA in the tail end of the Jim Crow era; and Dorothy Vaughan, another African American mathematician and “human computer” whose experience was chronicled in the 2016 film Hidden Figures It’s also a small but striking feature, echoing Mirzakhani’s diminutive stature and dazzling intellect. But most importantly, by proxy, I wanted to honour another woman who profoundly shaped my life as a scientist.

Crashing back down to a fractured planet

Sara Mazrouei is now a brilliant and multi-talented science communicator and education developer, but before that she was also a member of my lab at the University of Toronto. While my experience there was overwhelmingly positive, over the four years we worked together I witnessed Sara face many challenges—both in our department and in planetary science in general—simply for being a woman of colour. She was an exceptional scientist in addition to her teaching and outreach skills, but was often overlooked because of her background.

The most stark example of this came in 2016, when she was barred from a NASA facility during a summer internship, solely for being born in Iran. (You can listen to her first-hand account of this saga here). Hearing this story as it was happening to her, my naive impression of the universal and collaborative nature of science was utterly shattered; I just couldn’t imagine how they could do this to someone who had worked so hard and sacrificed so much to be there.

In the time since I’ve become increasingly aware of the many more injustices being committed on our fragile, precious planet, many—like in Sara’s case—simply because of where they were born. From the genocide in Gaza, to the (former) rule of terror in Syria, to the massacres in Sudan and Myanmar and Ukraine and Bangladesh, our world has been groaning under the weight of years of oppression, often as a direct consequence of actions in the West. We cannot afford (nor should we be justly allowed) to see these struggles as far-off foreign conflicts with no relation to us. Beyond their inherent

-xoxo gossip grad ☾⋆⁺₊⋆