14 Days

On October 7, I awoke to the news of the horrific slaughter and kidnapping that took place in southern Israel by members of Hamas. In the aftermath, as the initial paralyzing fear wore off, nobody was certain what exactly this would mean for the region going forward. I prayed that negotiations would be quick and result in an exchange of prisoners, as they have in times past, and that this blindsiding violence might give way to a renewed urgency in the call for peace and lasting agreements for the Palestinian and Israeli people. For as much as I can imagine that shock and pain experienced by the families of those killed or taken hostage that day, no one who has paid attention to this conflict since before that date could honestly claim it was unprovoked. 2023 had already been one of the deadliest years for Palestinians

Much to my own shame, I only really became aware of the plight of Palestinians in 2013, when controversy over a group called “Queers Against Israeli Apartheid” erupted for what was then the fourth year in a row. The group opposed the two-tiered legal and social system that existed in the occupied Palestinian territories, including separate roads, checkpoint procedures, and movement restrictions, and faced harsh backlash for their use of the word “apartheid” to describe this state of affairs. What had started in 2010 with a fight to simply be present in the parade had by 2013 evolved into a question over the city’s funding for Pride at all if the group were included, a decision which obviously caught the attention of little baby me planning to attend her first pride ever that year. In the end, funding was upheld, the group allowed to march, and I did go on to attend pride, but the seed was planted in my mind that there were some things about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that one was not allowed to say openly.

Over the next several years, I learned more about the history of the state of affairs in Palestine, especially after making several Palestinian friends and dating someone of Egyptian descent for a few years. And the more I learned, the more it became difficult to reconcile what I was hearing from people whose families had been directly affected by the conflict with the supposed “humanitarian” image portrayed by the Israeli government. I also met Israeli-Canadians and people with family in Israel, all of them queer, and all of them deeply skeptical of the progressive image the government had branded itself with in opposition to their “backwards” Muslim/Arab-majority neighbouring countries.

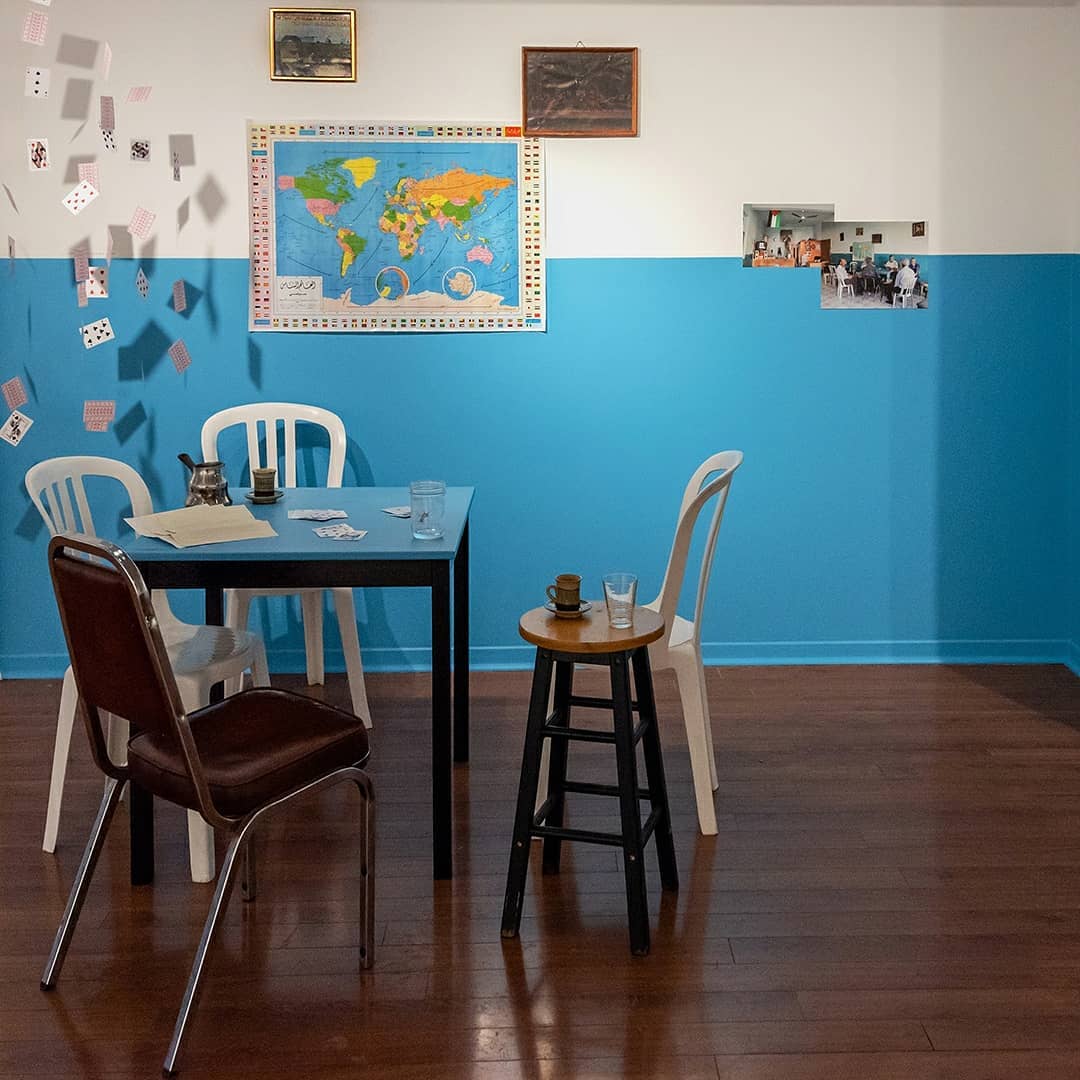

Then in early 2019 a friend of mine, Shatha Al-Husseini, put on an exhibition called “Loading Falasteen”[1]A video with snippets of the exhibition can be seen here. The sight of such casual and familiar items—a playing card table, deck carefully splayed out, where her father would spend days with his friends, a black-and-white photo of olive trees on a farm near where her mother grew up in Gaza, the road signs her parents passed by countless times, now committed to film from their first trip back as a family in 2016—brought this once-distant land into sharp and overwhelmingly emotional focus. So too did my ex’s experiences in Israel/Palestine, both on a Queer Birthright trip back in late 2015/early 2016 and a visit to the West Bank and Ramallah in early 2018, just before we met. This land was no longer a distant place of conflict and rhetoric and politics—it was alive, dancing with the spirit of all those I knew and loved who traced their origins there.

The flare-up of attacks in Sheikh Jarrah and al-Aqsa on the Temple Mount in 2021 felt like another turning point. It was difficult to watch the disproportionate violence rained down upon Palestinians, while the rest of the world remained silent, especially one year after the start of the 2020 Black Lives Matter George Floyd protests and the recognition of the interconnectedness of the struggles of all marginalized people, all the DEI statements and commitments to justice that had been put out since then.